At Co-create, we aim to be actively inclusive in all we do. This is really important to us, and drives a lot of our actions. But “being inclusive” has many meanings and uses. This short piece is an exploration of why we value inclusiveness and what it means in practice.

Why should we be inclusive?

The moral perspective feels a good place to start. It feels intuitively right that people have some opportunity to influence the institutions and structures that shape their individual experiences of the societies we share. “No decision about me without me” is a common claim to that right. At Co-create, we believe that people will be happier, and the world a better place, if we all have this opportunity.

Second, inclusive practice makes better stuff. OXO’s Good Grips kitchen tools are designed to be usable for people with limited manual dexterity, but work better for most people. Alfred Bird invented his eponymous custard as an egg-free version of the sauce because his wife was allergic to eggs. We see repeatedly in our work that more inclusive co-production practice leads to better outcomes (and outcomes that are better distributed amongst stakeholders).

Third, exclusive practice tends to exclude some more frequently than others. The harm created by exclusion from societies’ institutions and structures is compounded when we repeatedly exclude certain categories of people. It also leaves us with blind spots which can only harm our understanding and practice. Being inclusive helps to repair the damage of past exclusions, both as a demonstration that we care about redressing past wrongs and a method by which to be more equitable in the future.

So, how do we make ourselves as inclusive as possible?

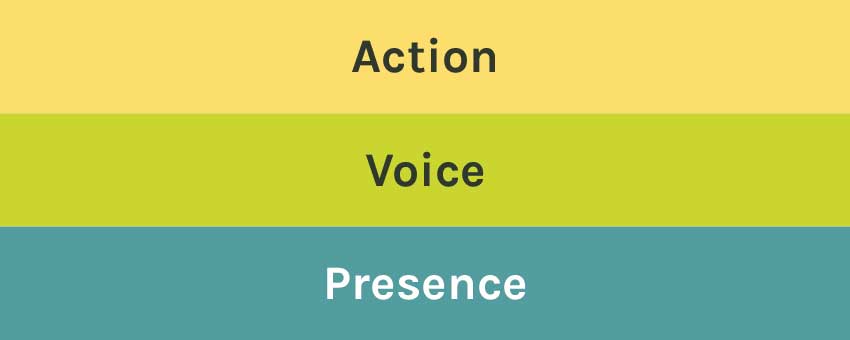

I’m going to think about this in terms of three layers, each building on the one below:

Presence

The foundational layer is probably the most obvious one. You can’t be included if you are not there (there are of course many ways of being “there”). When planning a new co-production project, Co-create start from the belief that everyone who might be affected by decisions made in a given space has the opportunity to attend (or for someone who they wish to represent them to attend). For this opportunity to be a genuine one, different people will need different types of support (travel costs, data costs, caring costs, compensation for time off work and so on).

Is it enough to simply offer the opportunity to everyone? For me, no. Imagine a healthcare provider wants to consult the people it serves on a new service. It runs some open workshops and a survey on its website. This will interest some people (generally those who get involved in a lot of these things) but leave many cold. Everyone here technically has the opportunity, but most will not have the motivation. This is something that co-production practitioners need to take some responsibility for. If your personal experience is that you and your community don’t get listened to (or people listen and then do nothing), would you give up your time to get involved?

Voice

The next layer of inclusiveness. In most groups of people, some voices are louder than others. There are often patterns which predict which voices are heard the most. Put simply, we are not doing inclusiveness any favours by inviting people to take part and then ignoring their input in favour of others. If as so often happens we plan to do something, put out a consultation survey, and then decide our original idea was best; have we really given the citizen a voice? How often does the voice of the citizen manage to speak as loud as that of the professional and create significant change to a plan?

Action

The final layer I’ll talk about here. When I work with organisations in health and social care, they have often identified that they aren’t hearing from as many people from ethnic minorities as they would like to. When I speak to people from ethnic minorities who have taken part in co-production and engagement of different sorts, I often hear that these questions have been asked and answered before, and nothing changed. Why would you put yourself through answering questions (some of which can be painful to answer) if you don’t trust that it will make any difference?

Diversity

Inclusiveness incorporates the important sociological categories such as gender and ethnicity which help to explain so much inequality in our world. But it also includes the more individual differences that make some spaces more welcoming or accessible than others. To genuinely be included, one person might need step-free access, another regular rest breaks, another a feeling of emotional safety.

Listening to individuals tell us about their needs also helps to future-proof our practice. Over the 20th and 21st centuries, we have (painfully slowly) included more categories of people in our understanding of inequality and exclusion. It would be ahistorical (and potentially arrogant) to assume that we now understand all the structural inequalities that exist between people and communities.

Where to begin

The challenges of being truly inclusive can feel insurmountable, which can put people off trying. How can we include everyone’s needs? There is no easy answer, and there is rarely a perfect solution. But for me we do pretty well if we can genuinely listen to what people tell us about their needs and wishes, be transparent about how we will address these needs (and where we expect to fail), and reflect with others on how we can improve and develop our practice for the future.